Scalable System Architecture

Case 1: The Trap of a Seemingly Scalable System Architecture

Why does this system architecture pattern seem cost-effective and infinitely scalable but is actually a massive trap that you should avoid at all costs? Please do not fall for this one unless you know the intricacies of this pattern. Why might I use this pattern for a toy side project that will likely never have any users or maybe just a handful of users? The reason might not be what you think. This is also one of the patterns I might use for applications that need to scale—those that need to handle hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of users. So, let’s break all this down.

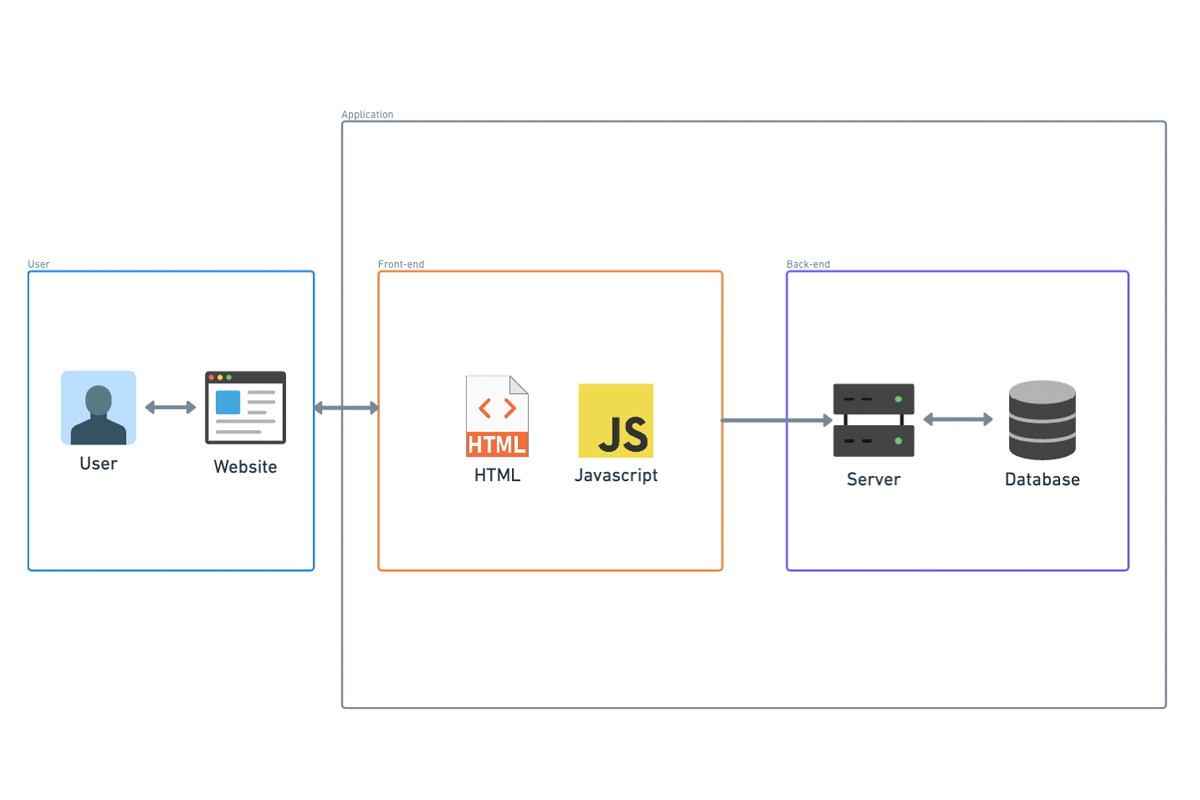

This basic system architecture is what everyone starts with, and there’s a pervasive argument that the vast majority of apps don’t need anything more than this. That’s kind of true, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that you should build this way. We’ll get to that.

In this scenario, you might not have an automated build process. Instead, you build on your local machine and manually copy the binaries to the host that will serve your application. Your scalability in this situation is limited to upgrading your cloud instance to a bigger one. To be fair, in terms of the ability to handle traffic, you could probably get pretty far with just one of the largest cloud instances available.

However, if you need to upgrade your infrastructure, you’re going to experience downtime. Even worse, every time you update your application, you’ll have downtime because you need to stop everything, copy the new binaries to the instance, and start your app again. Of course, that might not be a big deal if your original assertion that you don’t have many users is true.

In summary, this architecture pattern, while seemingly scalable and cost-effective, has significant drawbacks, especially concerning downtime during updates and infrastructure upgrades. This might be acceptable for small projects with minimal user bases, but for larger applications, its limitations could be problematic. Carefully consider the long-term implications and hidden costs of such architectural decisions.

Case 2: The Evolution to CI/CD

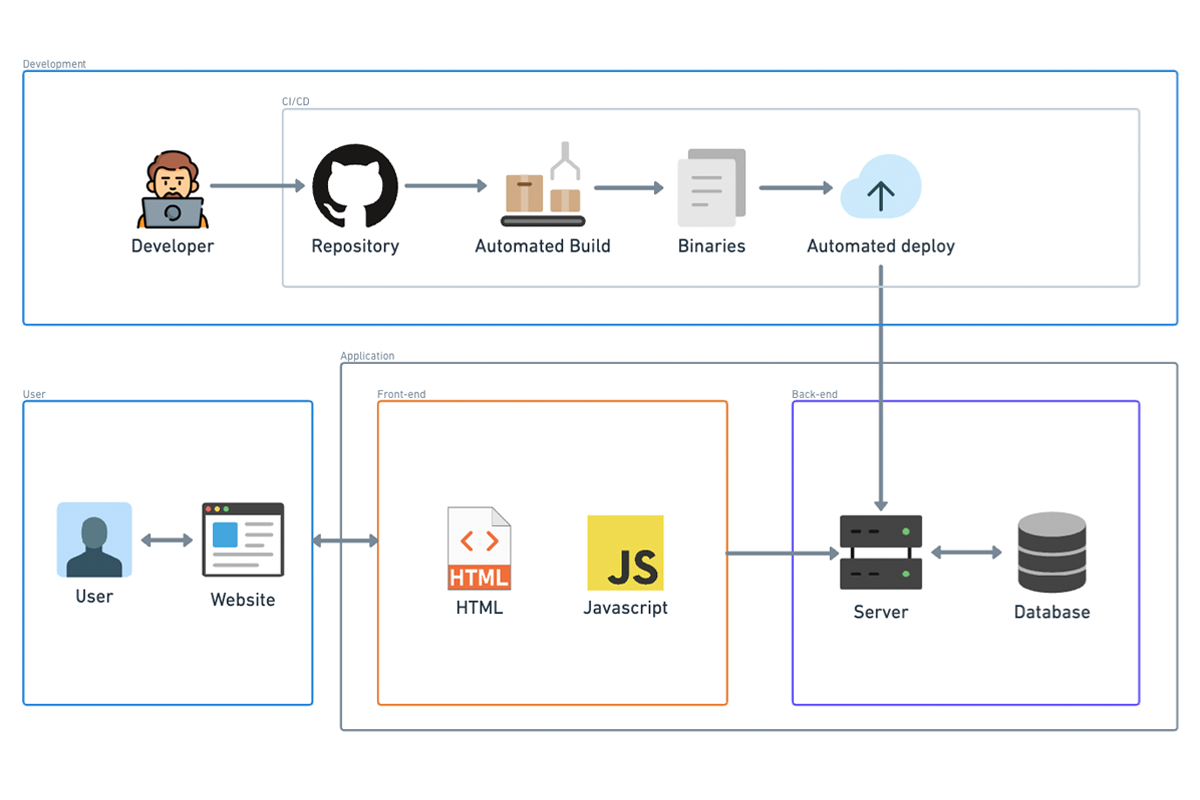

The next evolution in system architecture is adding CI/CD, or Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment. I almost didn’t mention this because, in this day and age, pretty much everyone is on board with this one. The lines between CI and CD can be a bit blurry, but generally speaking, here’s the breakdown.

Continuous Integration (CI):

- Automated Builds: When code is committed, an automated build is triggered. This means every time you push a change, the system compiles the code automatically.

- Automated Tests: After the build is complete, automated tests are run to ensure the new code doesn’t break existing functionality.

- Notifications: Developers receive notifications if either the build or tests fail, allowing them to quickly address issues. While CI might encompass other elements depending on the team or project, these three components form the core of CI.

Continuous Deployment (CD): Once the build completes and all tests pass, an agent automatically deploys the new application binary to the hosting platform. In this example, the deployment target is a plain EC2 instance. Often, automatic deployment first happens to a test environment rather than directly to production. Automated integration tests might run in this test environment to verify the application’s functionality in a setup that closely mirrors production.

Continuous Deployment vs. Continuous Delivery:

- Continuous Deployment: If the new binary is automatically deployed to production after passing the tests, this process is called continuous deployment.

- Continuous Delivery: In many cases, there is a manual approval step between deploying to the test environment and deploying to the production environment. If a human needs to approve and manually trigger the final deployment to production, it’s termed continuous delivery instead of continuous deployment. In summary, CI/CD represents a crucial evolution in modern software development, streamlining the process of integrating and deploying code changes. By automating builds, tests, and deployments, CI/CD helps maintain code quality and accelerates the delivery of new features and fixes, with the key distinction between continuous deployment and continuous delivery being the presence of a manual approval step before production deployment.

Case 3: The Advantages of Managed Hosting Platforms

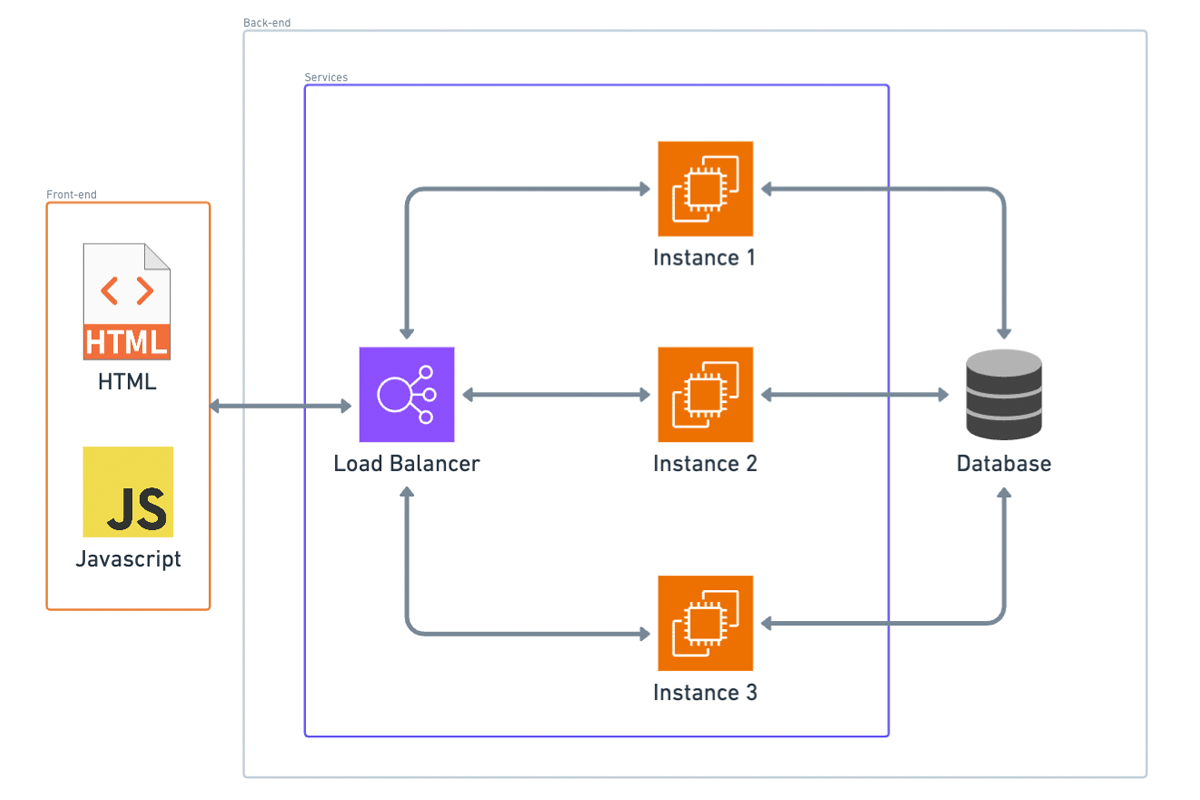

Now we start to get into managed hosting platforms. There’s nothing here that you couldn’t technically do manually, but the platform makes it way, way easier. Frankly, nobody I know of does this stuff manually anymore.

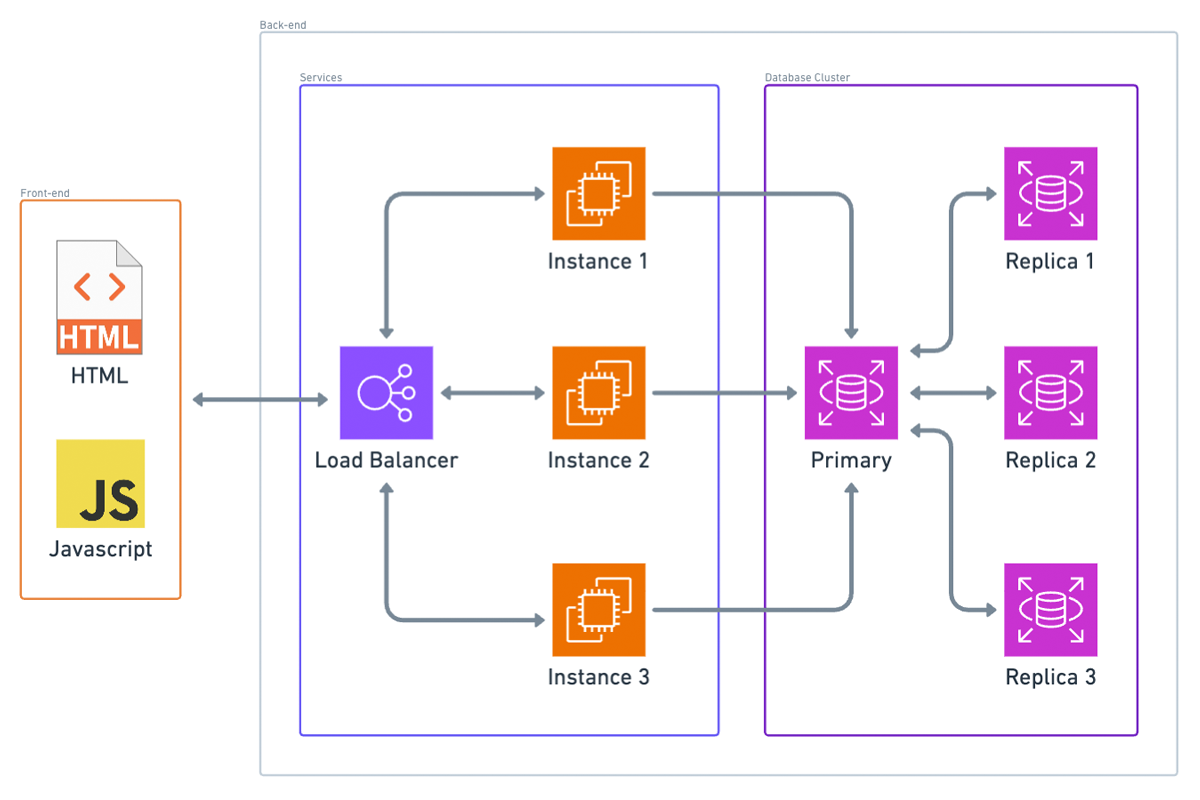

With managed hosting, we have a load balancer. The external world connects to your app through this load balancer, which distributes requests between one or more instances, each running your application. Here are the benefits:

1. Handling Higher Volume of Requests:

Your application can now handle a higher volume of requests than it could with just one instance. The load balancer distributes requests among the running instances using various strategies. Interestingly, random distribution of requests usually works fine.

2. Stateless Application Requirement:

For load balancing to work, your application needs to be stateless. This means it shouldn’t matter if different instances handle the client’s requests each time. Therefore, you can’t use in-memory caching or similar techniques that rely on state being preserved within a single instance.

3. Automatic Scaling:

Many deployment platforms, including AWS Elastic Beanstalk, support automatic scaling. This means you can set up rules for when scaling should happen, based on metrics like the number of requests or CPU usage. When the threshold for a metric is reached, the platform automatically creates another instance, deploys your application on it, and registers that instance with the load balancer to handle higher traffic volumes. For example, if three instances aren’t sufficient to handle the current traffic load, the system can automatically create a new instance, making a fourth instance. This fourth instance is then added to the load balancer, ensuring requests are distributed evenly across all four nodes.

In summary, managed hosting platforms offer significant advantages by simplifying tasks such as load balancing and scaling, allowing your application to handle increased traffic seamlessly. These platforms automate complex operations, enabling you to focus on developing your application rather than managing infrastructure intricacies.

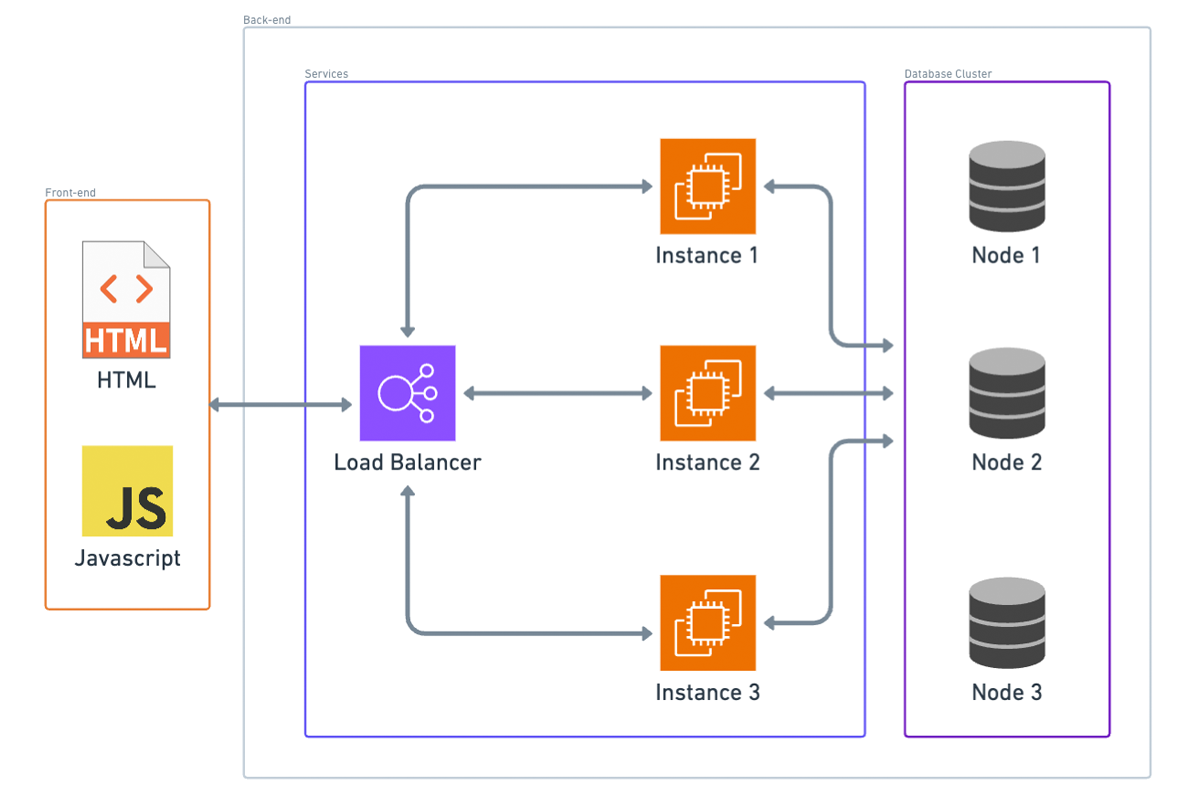

Case 4: Scaling the Database

At this point, we’re in a pretty good place, but it’s easy to see what the main bottleneck is now: the database. Scaling the database can be tricky if you haven’t planned for it from the beginning because it can impact how you design your schema.

Two Reasons for Database Scaling:

1. Data Size:

If your application’s data set can’t fit on one instance, you’ll need to implement sharding, which involves splitting your data across multiple database nodes. This process is complex. For instance, if you start with three nodes and need to add another, redistributing the data so that each node has an equal part can be challenging.

2. Traffic Volume:

The other reason to scale up the database is to handle higher traffic volumes. This involves distributing requests across nodes, similar to how we distribute requests to application instances behind a load balancer.

Key-Value or Document Databases:

If you chose a key-value or document database like AWS DynamoDB, scaling is much easier. These databases automatically handle fault tolerance, load balancing, and sharding of your data. Although they impose some constraints on your schema that wouldn’t exist with a SQL database, if your data structure allows, you should consider using one of these databases for easier scaling. To scale up or down, you might only need to change some configuration settings, if that, because these databases often have auto-scaling capabilities.

SQL Databases:

If you opted for a SQL database, scaling becomes more complex. However, if two conditions are met, you’ll probably be okay:

- Your application doesn’t require a high volume of writes.

- Your application’s entire data set can fit on one database instance.

If both are true, you can set up a single master, multiple replica database cluster. This setup typically doesn’t require changes to your application logic. In this configuration:

- All database writes are directed to the master instance.

- Read replicas receive state updates from the master whenever data changes.

- Read queries are load-balanced among these replica instances and, in some cases, the master as well.

However, the master database instance remains the bottleneck for writes. Additionally, the entire data set is copied to every instance, so if your data doesn’t fit on a single instance, this setup won’t be effective.

In summary, database scaling is crucial yet complex. Key-value and document databases offer automated solutions that simplify scaling, while SQL databases require more careful planning and configuration, especially when dealing with high volumes of writes or large data sets.

Case 5: The Fallacy of Not Building for Scale

Now that we have our potential endgame system architecture, there’s a fallacy I want to dispel in this video. This fallacy comes in various forms but is essentially the same idea: “I won’t have any users, so I don’t need to worry about scalability,” or “This is just a side project, so it doesn’t need to scale.”

The point I want to make is that even if your application won’t scale, it should scale, but not for the reasons you might think. It’s not necessarily because you might unexpectedly get more users than you can handle (you probably won’t). There’s more to it than that.

There’s a common misconception that building with scale in mind requires extra thought and will make every project take longer. While it does require some extra thought, that extra thought isn’t really on a per-project basis. Once you internalize the basic concepts around building for scale, I’d argue that building things with scale in mind doesn’t really add any extra scope to the project. It just takes a bit of time upfront to learn the concepts, and after that one-time investment, incorporating scalability into your project shouldn’t really add any scope. That’s my take anyway, and that’s why I think even toy or side projects should be built with scale in mind.

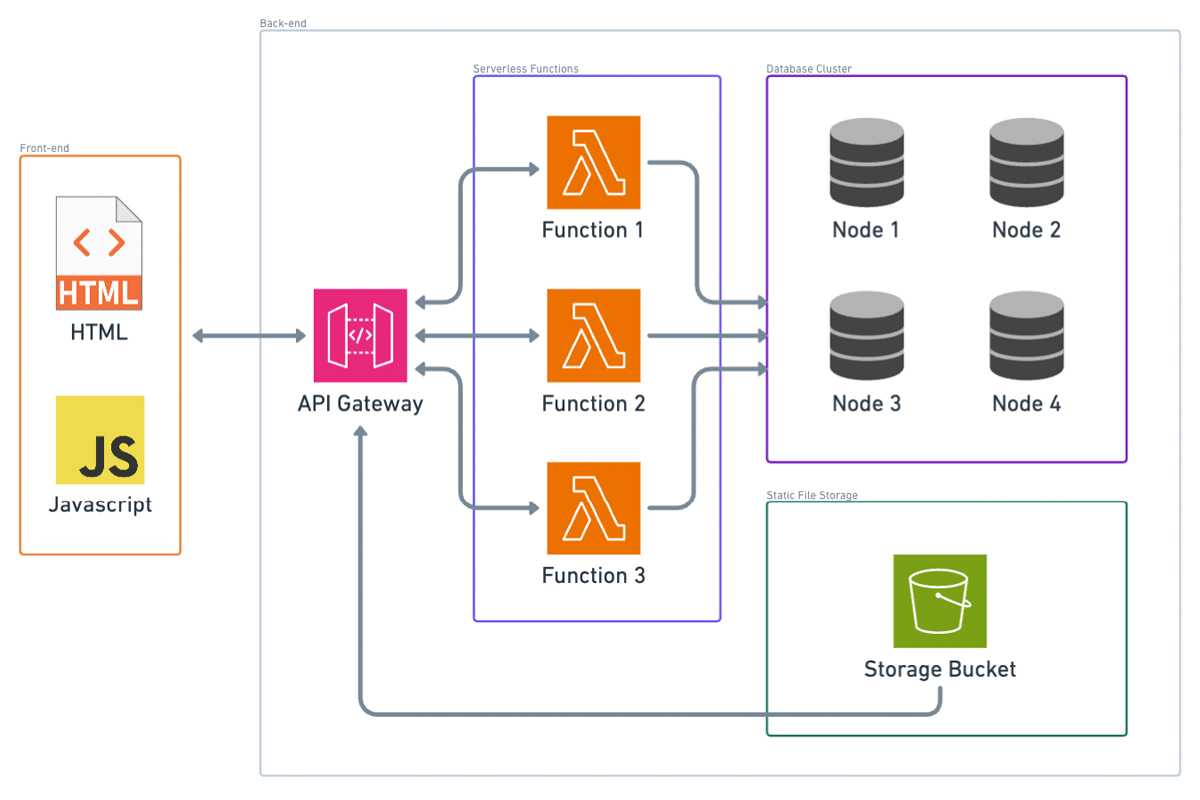

Case 6: Serverless Architecture

Next, let’s talk about serverless architecture. Here’s the serverless analog of what we’ve been doing so far. Instead of a load balancer, we have what you might think of as a lightweight proxy. In AWS, this would be API Gateway. Instead of our container platform, we have our static files (HTML and JavaScript) in an S3 bucket. For our APIs, we have serverless functions; in AWS, that would be AWS Lambda.

Notice that I took out the CDN box. You can still have a CDN if you configure API Gateway to be edge optimized, so that’s still kind of there.

Advantages of Serverless Approach:

Cost Efficiency:

If nobody’s using your application, the only thing you technically pay for is the static files in the S3 bucket and the data stored in your database (if you’re using a cloud database). If you’re using container instances, which likely use an EC2 instance per container, you’d be paying for that EC2 instance even if nobody’s making requests to it.

Elastic Scalability:

Serverless scalability is much more granular than in traditional architecture. Each instance in a container-based setup represents a certain number of requests per second it can handle. For example, each instance might handle 100 transactions per second, but if you need to handle 301 transactions per second at a certain time, you’d need four instances. You’d be paying for that fourth instance even though it’s almost not needed. Additionally, you need to set up your scaling criteria carefully. If traffic dies down and your containers don’t get spun down, you’re paying for extra containers you don’t need. Conversely, if traffic spikes and you don’t add more containers in time, you might face an outage.

Handling Sporadic Traffic:

Serverless functions excel at handling sporadic traffic. For example, if you suddenly get a thousand requests all at once after hours of no traffic, serverless functions should be able to handle it. You also pay on a per-request basis, so you’re always paying for exactly the amount of traffic you’re handling. Unless your traffic volume is consistently high, this is likely cheaper than the containerized equivalent.

In summary, even if your application is a side project or a small-scale application, building with scalability in mind can save you from future headaches and unexpected growth. Serverless architecture, in particular, offers cost efficiency and flexible scaling, making it a strong choice for many applications.

Database Replication Explained (in 5 Minutes)

Let’s talk about database replication for your system design interview.

Database replication is basically what it sounds like: copying data from one data source to another and thus replicating it in one or more places. There are many reasons for copying data: to protect against data loss during system failures, to serve increased traffic, or even to improve latency when pursuing a regional strategy. You can also think of replication as a proactive strategy to help applications scale. Ultimately, with data in modern distributed systems being spread out across multiple nodes and the fact that networks are notoriously unreliable, storing data in multiple places to prevent data loss has become absolutely essential.

Our focus today is going to be on the strategies that you can use to copy data specifically for databases, although a lot of these replication strategies are viable for other data sources too, like caches, app servers, and object file storage. Replication is simple if data doesn’t change much. Unfortunately, that’s not the case with most modern systems. So, how do write requests cascade across multiple identical databases with timeliness and consistency?

There are a few strategies to choose from, though as always, there are trade-offs for each. First, there is the leader-follower strategy, also known as primary replica. This is probably the most common strategy, where a query writes to a single designated leader. The leader then replicates the updated data to followers. Sounds simple enough, so what’s the catch? Well, if this is done synchronously, it can be really, really slow. Synchronous replication requires that both the leader and followers must commit before the write is considered successful. This does ensure that follower data is up to date, but if a follower in the chain goes down, the write query will fail. And even if the whole system is up, waiting for a follower located halfway across the world to come back up and acknowledge a successful write will raise latency considerably.

Asynchronous replication may be an option for use cases where transaction speed is more important than consistently accurate data. With asynchronous replication, the leader sends write requests to its followers and moves on without waiting for acknowledgment. Is this faster? Yes, but this introduces inconsistency between the leader and followers, which can be a huge problem if the leader goes down and the most up-to-date data is lost. And make no mistake, leader failures will happen. In the case of a simple leader-follower strategy, when the leader fails, which is also called a failover, the replica is promoted to be the leader and takes over. Failover is a huge problem under asynchronous replication, but it’s not great under synchronous replication either. Without a leader, you lose the ability to handle writes. It’s absolutely critical to talk through leader failure in your system design interview.

Luckily, there are a few tweaks to the base leader-follower framework that can help. Our next strategy tweaks leader-follower by designating more than one leader in the system. This is called leader-leader or multi-leader, and it’s a simple way to mitigate leader failure. In this strategy, more than one database is available to take writes, meaning if one leader goes down, the other can step in. In order to figure out which one steps in, we use different types of consensus algorithms to elect a new leader. The most common consensus algorithm out there is Paxos, which you may have already heard of. This multi-leader strategy does introduce a slight lag as data must be replicated to multiple leaders, and engineers need to deal with that complexity, especially when discrepancies arise between leaders. But the added durability mostly outweighs the cons.

Next, we have leaderless replication. Why maintain the leader-follower hierarchy at all if leader election and conflict resolution are so painful? Amazon’s DynamoDB repopularized the idea of leaderless replication, and now most cloud providers use something similar. A lot of people consider leaderless replication to be pure anarchy, but there are some clever methods for dealing with the chaos that comes with managing a network of read and write capable replicas. For example, with read repair, clients can detect errors when several nodes return a consistent value but one doesn’t. These errors are then fixed by sending a write request to the inconsistent node.

Now that we know a few replication strategies, how do you know when to implement one? There are so many reasons to include replicas and so many strategies to choose from. We generally recommend including replicas in anything more than the most basic server database system. The key is choosing the right strategy. To learn more, check out the Exponent article linked in the description to get more in-depth about each of these strategies and the best time to use them. Good luck with your interviews and thanks for watching.

The Basics of Database Sharding and Partitioning in System Design

What is database sharding?

Traditionally, data has been stored in an RDBMS or relational database management system. Data is stored in tables as rows and columns. For data with one-to-many or many-to-many relationships, a process of normalization would instead store the data in separate tables joined together by foreign keys, which ensure that the data in these tables does not get out of sync with each other and can be joined to get a complete view of the data.

However, as data size increases, traditional database systems run into bottlenecks on CPU, memory, or disk usage. They will need increasingly high-end and expensive hardware in order to maintain performance. Even with top-quality hardware, the data requirements of most successful modern applications far exceed the capacity of a traditional RDBMS.

Sometimes, the structure of the data is such that the tables holding data can be broken up and spread across multiple servers. This process of breaking up large tables into horizontal data partitions, each of which contains a subset of the whole table and putting each partition in a separate database server, is called sharding. Each partition is called a shard.

Sharding Techniques

Most times, the technique used to partition data will depend on the structure of the data itself. A few common sharding techniques are:

Geobased Sharding: Data is partitioned based on the user’s locations, such as the continent of origin or a similarly large area like East U.S. or West U.S. Typically, a static location is chosen, such as the user’s location when their account was created. This technique allows users to be routed to the node closest to their location, thus reducing latency. However, there may not be an even distribution of users in the various geographical areas.

Range-based Sharding: Range-based sharding divides the data based on the ranges of the key value. For example, choosing the first letter of the user’s first name as the shard key will divide the data into 26 buckets, assuming English names. This makes partition computation very simple, but it can lead to uneven splits across data partitions.

Hash-based Sharding: Hash-based sharding uses a hashing algorithm to generate a hash based on the key value and then uses the hash value to compute the partition. A good hash algorithm will distribute data evenly across partitions, thus reducing the risk of hotspots. However, it is likely to assign related rows to different partitions, so the server can’t enhance performance by trying to predict and preload future queries.

Manual vs. Automatic Sharding

Some database systems support automatic sharding. The system will manage the data partitioning. Automatic sharding will dynamically repartition the data when it detects an uneven distribution of the data or queries among the shards. This leads to higher performance and better scalability. Unfortunately, many monolithic databases do not support automatic sharding. If you need to continue using these databases but you have increasing data demands, then the sharding needs to be done at the application layer. However, this has some significant downsides.

One downside is a significant increase in development complexity. The application needs to choose the appropriate sharding technique and decide the number of shards based on the projected data trends. If those underlying assumptions change, the application has to figure out how to rebalance the data partitions at runtime. The application has to figure out which shard the data resides in and how to access that shard. Another challenge with manual sharding is it sometimes results in an uneven distribution of data among the shards. This is especially true as data trends differ from what they were when the sharding technique was chosen. Hotspots created due to this uneven distribution can lead to performance issues and server crashes. If the number of shards chosen initially is too low, repartitioning will be required in order to address performance regressions as data increases. This can be kind of tough, especially if the system needs to have no downtime. Operational processes, such as changes to the database schema, also become rather hard. If schema changes are not backward compatible, the system will need to make sure that all shards have the same schema copy and the data is migrated from the old schema to the new one correctly on all shards.

Advantages of Sharding

Let’s talk about some advantages of sharding. First, sharding allows a system to scale out as the size of the data increases. It allows the application to deal with a larger amount of data than can be done using a traditional RDBMS. Second, having a smaller set of data in each shard also means that the indexes on that data are smaller, which results in faster query performance. Next, if an unplanned outage takes down a shard, the majority of the system remains accessible while that shard is restored. Downtime doesn’t take out the whole system. Finally, smaller amounts of data in each shard mean that the nodes can run on commodity hardware and do not require expensive high-end hardware to deliver acceptable performance.

Disadvantages of Sharding

The disadvantages of sharding also exist. Not all data is amenable to sharding. Foreign key relationships can only be maintained within a single shard. Manual sharding can be very complex and can lead to hotspots. Because each shard runs on a separate database server, some types of cross-shard queries, such as table joins, are either very expensive or just not possible. Once sharding has been set up, it’s very hard, if not impossible on some systems, to undo sharding or to change the shard key. Each shard is a live production database server, so you need to ensure high availability via replication or other techniques. This increases the operational cost compared to a single RDBMS.

And there you have it. I hope this video gave you a better sense of what sharding is and how it works.

Load Balancer for System Design Interviews

Why do we need load balancers?

To understand how and why load balancers are used, it’s important to remember a few concepts about distributed computing. First, web applications are deployed and hosted on servers. These applications live on hardware machines with finite resources such as memory, processing power, and network connections. As the traffic to an application increases, these resources can become limiting factors and prevent the machine from serving requests. This limit is known as the system’s capacity.

At first, some of these scaling problems can be solved by simply increasing the memory or CPU of the server or by using the available resources more efficiently, as is the case for something like multi-threading. At a certain point, though, increased traffic will cause any application to exceed the capacity that a single server can provide. The only solution to this problem is to add more servers to the system, also known as horizontal scaling.

When more than one server can be used to serve a request, it becomes necessary to decide which server to send the request to. That’s where load balancers come in.

How do load balancers work?

A good load balancer will efficiently distribute incoming traffic to maximize the system’s capacity and minimize the time it takes to fulfill the request. Load balancers can distribute traffic using several different strategies:

Round Robin: Servers are assigned in a repeating sequence so the next server assigned is guaranteed to be the least recently used.

Least Connections: This assigns the server currently handling the fewest number of requests.

Consistent Hashing: Similar to database sharding, the server can be assigned consistently based on IP address or URL.

Since load balancers must handle the traffic for the entire server pool, they need to be efficient and highly available. Depending on the chosen strategy and performance requirements, load balancers can operate at higher or lower network layers, such as HTTP or TCP. They can even be implemented in hardware. Engineering teams typically don’t implement their own load balancers. Instead, they use an industry standard reverse proxy like HAProxy or Nginx to perform load balancing and other functions such as SSL termination and health checks. Most cloud providers also offer out-of-the-box load balancers such as Amazon’s Elastic Load Balancer.

When should you use a load balancer?

You should use a load balancer whenever you think the system you’re designing would benefit from increased capacity or redundancy. Often, load balancers sit right between external traffic and the application servers. In a microservice architecture, it’s important to use load balancers in front of each internal service so that every part of the system can be scaled independently.

Be aware, though, that load balancing cannot solve many scaling problems in system design. For example, an application can also succumb to database performance, algorithmic complexity, and other types of resource contention. Adding more web servers won’t compensate for inefficient calculations, slow database queries, or unreliable third-party APIs. In these cases, designing a system that can process tasks asynchronously, such as a job queue, may be necessary.

Keep in mind that load balancing is distinct from rate limiting, when traffic is intentionally throttled or dropped to prevent abuse by a particular user or organization.

Advantages of Load Balancers

Scalability: Load balancers make it easier to scale up and down with demand by adding or removing backend servers.

Reliability: Load balancers provide redundancy and can minimize downtime by automatically detecting and replacing unhealthy servers.

Performance: By distributing the workload evenly across servers, load balancers can improve the average response time.

Considerations when using a Load Balancer

As scale increases, load balancers can themselves become a bottleneck or single point of failure. Multiple load balancers must be used to guarantee availability. DNS round robin can be used to balance traffic across different load balancers. Additionally, the same user’s requests can be served from different backends unless the load balancer is configured otherwise. This could be problematic for applications that rely on session data that isn’t shared across servers. Finally, deploying new server versions can take longer and require more machines. This is because the load balancer needs to roll over traffic to the new servers and drain requests from the old machines.

And there you have it, an overview of load balancers and how to build more scalable web applications.

Database Caching for System Design Interviews

Introduction to Caching

Caching is a data storage technique that plays an essential role in designing scalable internet applications. A cache is any data store that can store and retrieve data quickly for future use. This enables faster response times and decreases the load on other parts of your system.

Why do we need caching?

Without caching, computers and the internet would be impossibly slow due to the access time of retrieving data at every step. Caches take advantage of a principle called locality to store data closer to where it is likely to be needed. In a broader sense, caching can also refer to storing pre-computed data that would otherwise be difficult to serve on demand, such as in personalized news feeds or analytics reports.

How does caching work?

-

In-memory application cache: Storing data directly in the application’s memory is a fast and straightforward option. However, each server must maintain its own cache, increasing overall memory demands and the cost of the system.

-

Distributed in-memory cache: A separate caching server, such as Memcached or Redis, can store data so that multiple servers can read and write from the same cache.

-

File system cache: This cache stores commonly accessed files. CDNs (Content Delivery Networks) are an example of a distributed file system that takes advantage of geographic locality.

Caching Policies

If caching is so great, why not cache everything? There are two main reasons: cost and accuracy.

Since caching is meant to be fast and temporary, it’s often implemented with more expensive and less resilient hardware than other types of storage. For this reason, caches are typically smaller than the primary data storage system. They must selectively choose which data to keep and which to remove or evict.

Selection Process (Caching Policy)

The selection process, known as a caching policy, helps the cache free up space for the more relevant data that will be needed. Some examples of caching strategies include:

-

First In, First Out (FIFO): This policy evicts the item that was added the longest ago and keeps the most recently added items.

-

Least Recently Used (LRU): This policy keeps track of when items were last retrieved and evicts the item that has not been accessed recently.

-

Least Frequently Used (LFU): This policy tracks how often items are retrieved and evicts the item used least frequently, regardless of when it was last accessed.

Cache Coherence

One final consideration is how to ensure appropriate cache consistency.

-

Write-through cache: Updates the cache and main memory simultaneously, ensuring no chance of inconsistency. This also simplifies the system.

-

Write-behind cache: Memory updates happen asynchronously, which may lead to inconsistency but significantly speeds up the process.

-

Cache-aside (lazy loading): Data is loaded into the cache on demand. First, the application checks the cache for requested data. If the data is not in the cache, the application fetches it from the data store and updates the cache. This simple strategy keeps the data in the cache relatively relevant, especially if you choose a cache eviction policy and limited TTL (Time To Live) combination that matches data access patterns.

Decisions when designing a cache

When designing a cache, you’ll need to make three big decisions:

- How big should the cache be?

- How should I evict cache data?

- Which expiration policy should I choose?

Conclusion

I hope this overview gave you a better sense of what caching is and how it works. For more interview prep content, Exponent offers the best resources to help you ace your system design and software engineering interviews, including in-depth interview courses, private coaching, and a community of experts ready to help you prep for even the toughest questions.

CDNs in High-Performance System Design

Introduction to CDNs

Imagine a company is hosting a website on a server in an AWS data center in California. It may take around 100 milliseconds to load for users in the US, but it takes three to four seconds to load for users in China. Fortunately, there are strategies to minimize this request latency for users that are far away, and you always have to keep these strategies in mind when designing or building systems on a global scale.

What are CDNs?

CDNs, or Content Distribution and Delivery Networks, are a modern and popular solution for minimizing request latency when fetching static assets from a server. An ideal CDN is composed of a group of servers spread out globally. Hence, no matter how far away a user is from your server, they’ll always be close to a CDN. Instead of having to fetch static assets like images, videos, HTML, CSS, and JavaScript from the origin server, users can quickly fetch cached copies of these files from the CDN. Static assets can be quite large in size, such as an HD wallpaper image. By fetching that file from a nearby CDN server, a lot of network bandwidth is saved.

Popular CDNs

Cloud providers typically offer their own CDN solutions since it’s so popular and easy to integrate with their other service offerings. Some popular CDNs include:

- Cloudflare CDN

- AWS CloudFront

- GCP Cloud CDN

- Azure CDN

- Oracle CDN

How do CDNs work?

A CDN is a globally distributed group of servers that cache static assets from your origin server. Every CDN server has its own local cache, which should all be in sync. There are two primary ways for a CDN cache to be populated, creating a distinction between push and pull CDNs.

Push and Pull CDNs

- Push CDN: Engineers must push new or updated files to the CDN, propagating them to all the CDN server caches.

- Pull CDN: The server cache is lazily updated. When a user sends a static asset request to the CDN server and it doesn’t have it, the CDN server fetches the asset from the origin server, populates its cache with that asset, and then sends it to the user. If the CDN has the asset in its cache, it returns the cached asset.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Push CDN:

- Advantages: Ensures that assets are always up-to-date.

- Disadvantages: More engineering work for developers to maintain.

Pull CDN:

- Advantages: Requires less maintenance since the CDN automatically fetches assets from the origin server that are not in its cache.

- Disadvantages: The CDN cache may become stale after assets are updated on the origin server. The first request to a pull CDN will always take longer since it has to fetch the asset from the origin server.

Despite the disadvantages, pull CDNs are more popular because they’re easier to maintain. Several methods can reduce the time a static asset is stale, such as attaching a timestamp to cached assets and caching them for up to 24 hours by default. Cache busting, where assets are cached with a unique hash or e-tag compared to previous versions, is another solution.

When should you not use CDNs?

CDNs are generally beneficial for reducing request latency for static files but not for most API requests. However, there are situations where you should not use CDNs:

- If your service targets users in a specific region, there is no benefit to using a CDN; you can host your origin servers there instead.

- CDNs are not suitable for serving dynamic and sensitive assets, such as when working with financial or government services, where serving stale data could be problematic.

Example Interview Question

An example interview question about CDNs might be: Imagine you’re building Amazon’s product listing service, which serves a collection of product metadata and images to online shoppers’ browsers. Where would a CDN fit in the following design? You can answer in the comments below and let us know what you think.

Conclusion

I hope this video gave you a little bit of insight into CDNs and how they work.